How should an investment advisor think about building a portfolio for clients? Or how should an investor think about building a portfolio for themselves? Many investors agree that a balance between stocks and bonds is fundamental to optimal portfolio construction. But there may be less agreement about other questions – passive vs. active, alternatives vs. traditional asset classes.

We at Counterpoint believe in a few principles that we think all advisors and investors should consider when managing assets.

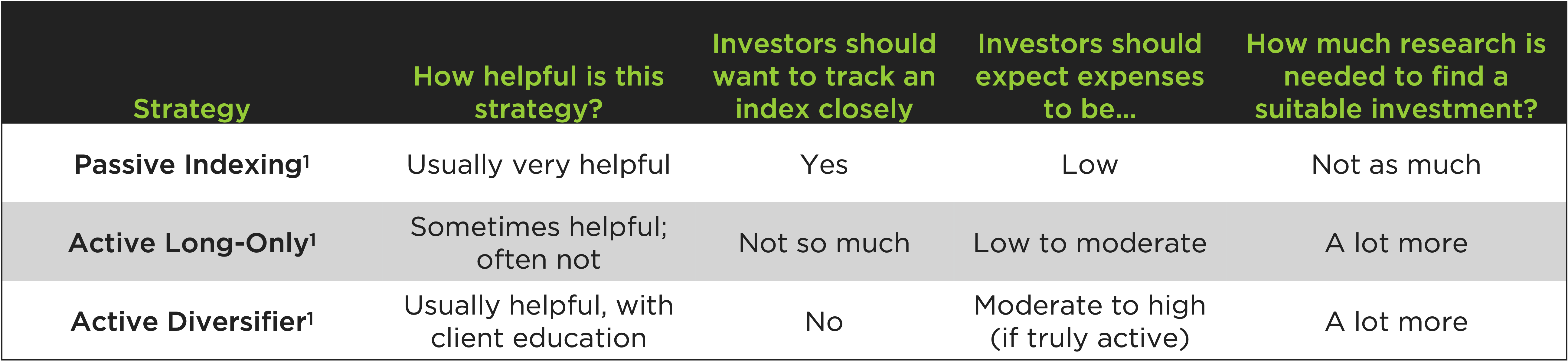

Looking at the rubric above, we believe the optimal investment portfolio usually avoids actively managed long-only investment strategies, and instead combines passive/cheap beta1 exposure with actively managed diversifiers.

Does buying cheap/passive indexes actually work?

It might seem a little surprising to hear a quantitative investment manager recommend holding passive index exposure, but the evidence for passive investing is substantial.

Passive strategies have come to dominate the investment world since legendary investor and Vanguard founder John Bogle (1929 – 2019) started his first index fund in the mid-1970s. Bogle believed that low cost and broad market exposure were the keys to success, not the high fees that often accompanied actively managed funds.

“Don’t let the miracle of long-term compounding of return be overwhelmed by the tyranny of long-term compounding of costs.“

– John Bogle

The inventor of the first S&P 500 index fund prophesied that investors would be better off investing in low-cost, highly diversified passive portfolios that make no effort to outperform (“cheap beta”). In the ensuing decades, this has been largely proven correct with evidence and investment piling up in support of this argument. Passive index funds offer broad market diversification and systematic exposure at a low enough cost that many investors find attractive.

We agree: Passive index exposure is a great way for investors to take advantage of ongoing technological progress, the tendency for economies to grow, and companies’ habit of historically generating reasonable returns on capital in exchange for a certain amount of risk.

Be skeptical of long-only active management, especially discretionary management1.

The rationale for passive investing hints at why we at Counterpoint mostly discourage “long-only” active investing that closely tracks an index. We believe it’s very difficult to beat indexes simply by picking individual stocks or bonds whose returns are, on average, mostly dictated by the direction of the overall market.

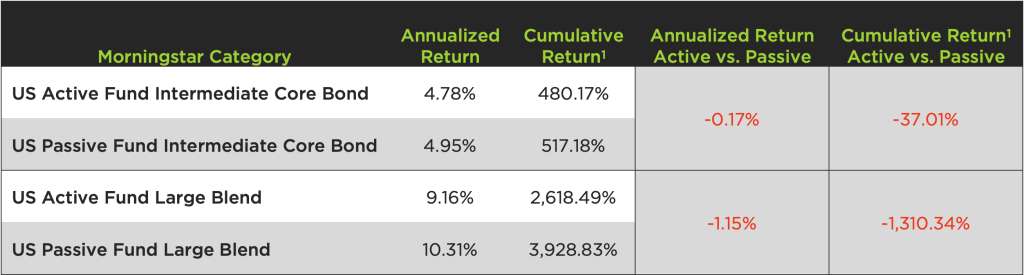

Instead, long-only active management can generate greater expenses, which drag on long-term returns. The table below compares annualized returns to passive indexes and their actively managed counterparts, as represented by Morningstar categories.

Performance of Actively Managed vs. Passively Managed Long-Only Funds:

01/01/1987 to 8/31/2024

Basically, fixed income investors on average lost 17 bps of annualized return vs. passive. US active long-only stock investors gave up 1.15% annually vs. what they would have earned in comparable passive vehicles.

To get results that are different from those of the market, a manager should be doing something really different – running a very concentrated equal weight portfolio, going “short” stocks alongside long investments, or taking a highly tactical approach by shifting into and out of different asset classes.

Long-only active strategies have another potential weakness. Many long-only managers rely on discretionary processes that can be subject the same cognitive biases and emotions that can lead to suboptimal investment outcomes.

Get active, but when you do, get active for the right reason.

We said it already: Differentiated results require a differentiated investment approach. Passive investing is a great starting point for many investors.

Active investing should be aimed toward generating returns that behave differently from passive investing. In technical terms, active strategies should have high tracking error or active share, and low correlation. They should move differently.

Counterpoint was founded under the belief that investments (aka diversifier strategies) that move differently from the other asset classes held by a portfolio are a key means to diversify and manage risk. Indexes sometimes have down periods; investments that seek differentiated returns from indexes can create greater opportunities to be down less, be flat, or even sometimes be up when broad markets are suffering.

Here are examples of very active strategies we believe in:

- Tactical asset allocation that systematically seeks to manage downside risk.

- Long-short equity investment that seeks to identify mispricing in stocks and create portfolios of stocks with no correlation to the stock market.

- Systematic high active share long equity investment that creates a highly differentiated portfolio vs. market-weighted benchmarks.

It’s important to note that investment strategies seeking this differentiated behavior can often be more expensive due to their unique approaches. The investor’s job is to hold such managers accountable, and make sure they are getting what they pay for.

Conclusion

For many investors, we believe the optimal portfolio consists of a blend between low-cost passive investment and carefully vetted highly differentiated active alternatives. Counterpoint leverages this approach to portfolio management by managing highly differentiated active strategies and by advising clients on general portfolio construction. The key is to take broad market risk, and simultaneously manage that risk via a systematic approach to maximally active investment strategies.