Investors pay professional money managers because of managers’ reputation for identifying and exploiting mispriced assets in an effort to beat the market. However, recent evidence shows that institutional investors on average miss out on meaningful, persistent, and well-documented opportunities to outperform passive index strategies.

Academic research has found evidence of numerous investment “anomalies.” Anomalies occur when stock prices appear to be incorrect. Their existence contradicts the famous Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), which says that asset prices correctly reflect available information. Therefore, anomalies may serve as evidence that investors can use available information to beat the market.

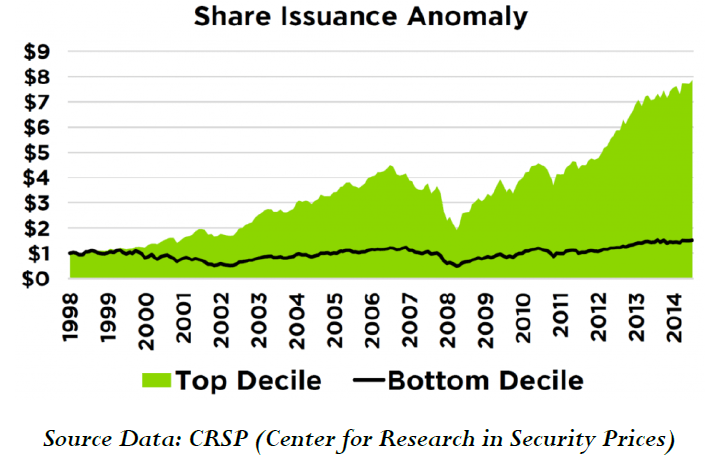

One example is the share issuance anomaly, first documented by Tim Loughran and Jay Ritter in the Journal of Finance in 1995. Loughran and Ritter show that firms which have recently issued stock through IPOs or secondary offerings have low stock returns in the next 3-5 years.

The Share Issuance Anomaly figure above represents the total compounded return on $1 invested initially in December of 1998 in a monthly rebalanced even-weighted portfolio without transaction costs of U.S. stocks deciled by total share issuance estimates. Share issuance is defined as the annual percentage of new shares issued over the prior fiscal year. Top Decile represents the 10% of stocks with the lowest share issuance while Bottom Decile represents the 10% of stocks with the highest share issuance. Past Performance does not guarantee future results.

This violates the EMH; it appears investors can use available information (i.e., whether firms have issued stock) to construct a strategy that beats the market: Buy firms that have not issued (or even bought back) stock, and sell short firms that have. The idea is that firm managers know more about their companies’ prospects than outside investors do, and this creates an exploitable mismatch: When managers issue shares, they send a negative signal that the market does not fully appreciate.

Over the past 40 years there have been dozens of anomalies documented in the academic literature: from share issuance (Loughran and Ritter, 1995) to momentum (Jegadeesh and Titman, 1993) to asset growth (Cooper, Gulen and Schill, 2008). Given many of these anomalies have been around for a long time – and replicated many times in academic studies — a natural question arises: do institutional money managers, on average, take advantage of these anomalies in their own portfolios?

The answer is “No.”

This was the eyebrow-raising finding in “Institutional Investors and Stock Return Anomalies” by Roger Edelen, Ozgur Ince and Greg Kadlec, which is forthcoming in the Journal of Financial Economics. Edelen et al. examine the quarterly 13F forms that list the long holdings of each institutional money manager with more than $100 million in assets. Then they look at changes in these 13F holdings over a 30-year period (1982-2012) to see whether institutional money managers are buying up stocks that seven anomaly signals say you should buy (long), sell (short) or leave alone (neutral).

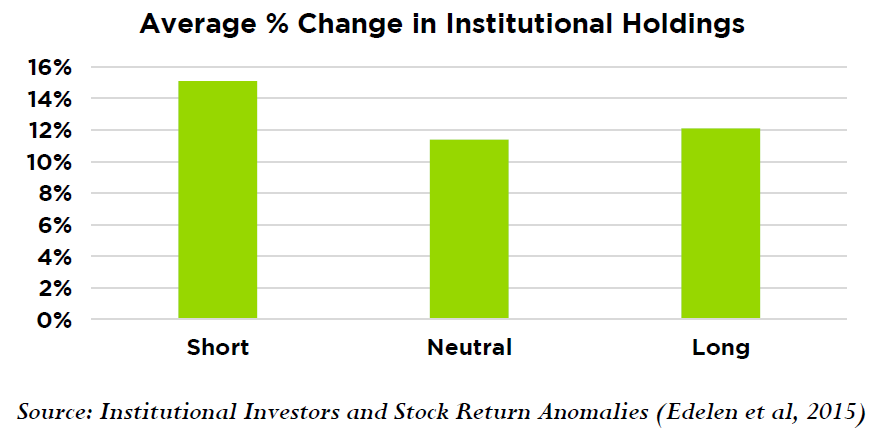

Surprising fact: institutional money managers, on average, buy the wrong stocks! You can see it in the picture below which is derived from Table 4 of their paper:

This figure plots the average percent change in the number of institutional owners of long, neutral, and short anomaly stocks during the period in which the anomaly information becomes available. The fact that all three bars are positive suggests that the number of institutional investors was increasing during the thirty-year period they examine (1982-2012).

What’s interesting, however, is that the average increase in institutions holding long-anomaly stocks is 12.1% but the average increase in institutions holding short-anomaly stocks is 15.1%. That is, as institutions increase their holdings, they are, on average, more likely to buy stocks that anomaly signals say are a mistake.

Our takeaway from this research is that, even though many anomalies have been known for a while, there are still plenty of investors who don’t act on them. Moreover, many of the signals which underlie anomalies – like asset growth or market-to-book – are like “honey traps,” stock characteristics that might tantalize investors into buying stocks that they shouldn’t.

While it isn’t a surprise to find that individual investors often buy the wrong stocks, it is perhaps unexpected the average institutional investor falls into these honey traps as well. We think this bodes well for investors in active strategies that seek to capture alpha from anomaly exposure.

Disclosures

The material provided herein has been provided by Counterpoint Mutual Funds, LLC and is for informational purposes only. Counterpoint Mutual Funds, LLC serves as investment adviser to one or more mutual funds distributed through Northern Lights Distributors, LLC member FINRA. Northern Lights Distributors, LLC and Counterpoint Mutual Funds, LLC are not affiliated entities.

4288-NLD-4/19/2016